Senthil Nayagam has been besotted with actor Suriya for weeks. He has downloaded interviews and speeches of the actor, and has been feeding them to his many AI (artificial intelligence) tools in an attempt to “master Suriya’s voice”.

“Let’s try running it now,” says Senthil, rubbing his hands in glee as he quickly taps his laptop. He selects one of his favourite Ilaiyaraaja songs – ‘Nilave Vaa’, sung by SP Balasubrahmanyam, in the 1986 Tamil film Mouna Raagam – and presses some more keys.

Within a few seconds, the familiar strains of ‘Nilave Vaa’ play out, sung in Suriya’s distinct voice!

An AI-generated image of what could be the ultimate blockbuster: a film starring Rajinikanth and Kamal Haasan

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

All this stemmed from when Senthil asked himself a question a few months ago: Can I replace one person with another? Following that train of thought, he made the late SP Balasubramanyam sing the ‘Rathamaarey’ song, originally sung by Vishal Mishra, from Rajinikanth’s recent hit Jailer.

Senthil then went one step further; he used a face-swapping technique to replace Tamannaah with Simran for the foot-tapping ‘Kaavala’, Anirudh’s hit song from Jailer, a short video that generated more than 2 million views, especially after the two actresses also shared it.

For Senthil, who currently runs a generative AI company called Muonium Inc, AI is “a toy he is experimenting with”. Currently, he is making use of the technology to create a voice similar to AR Rahman’s to sing all the songs that he has composed, like ‘Usurey Poguthey’ from Raavanan, which was performed by singer Karthik. “This is actual work,” he admits, “We need to separate the instruments and the voice, clean any noise and then mix it back. I’ve got mixed feedback for my content, because some fans aren’t happy with the videos featuring people who have passed on. But audiences should understand that the possibilities with AI are exciting.”

It is. AI is slowly creeping into various facets of Tamil cinema, changing the way filmmakers vision and execute their projects. Like Senthil, there are many others dabbling in AI. Like Teejay-Sajanth Sritharan, for instance. A Srilankan Tamil living in the UK, he has also created voice models for many leading Tamil actors.

Using AI tools like Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, Chat GPT or a combination of Python and GPU, these AI creators are not just putting their work out there for audiences, but also collaborating with producers and directors.

Lyricist-dialogue writer Madhan Karky used multiple AI tools for his upcoming Suriya-starrer Kanguvafor concept designs and world building. “I also use AI as my writing assistant when I write stories or scenes. It saves a lot of time, because we have tools like Kaiber and Gen-2 that can create animation and lyric videos,” says the lyricist.

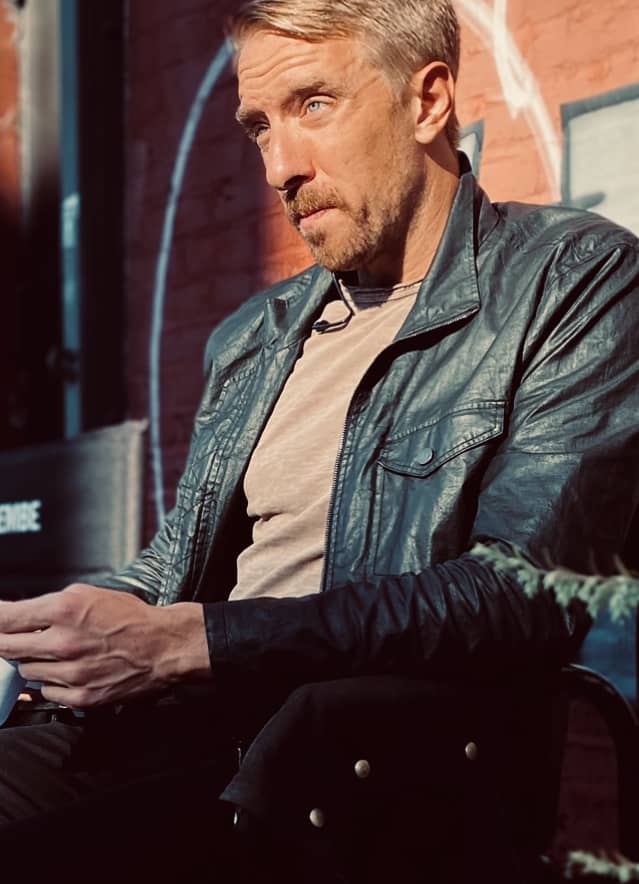

Suriya in a still from ‘Kanguva’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Using a tool called SongR, Madhan created ‘En Mele’, the world’s first AI-composed Tamil song, now available on leading music streaming platforms. “I had to make it learn Tamil, which was very challenging,” he says, adding “In a few years, most AI tools will become well-versed in all languages in the world.”

Karky has another prediction: that, within a year, a movie completely generated using AI will release in theatres.

While that may take a while, in November, audiences will be able to watch about four minutes of AI-generated content in Tamil film Weapon, starring Sathyaraj. The makers decided to opt for this during the post-production stage, when they felt that a flashback portion would add value to the film. Using a software developed by the team, director Guhan Senniappan and team fed photos of the leads (Sathyaraj and Vasanth Ravi) to generate the sequences.

“It saves a lot of time,” says Guhan, who has previously worked on Sawaari (2016) and Vella Raja (2018), “Earlier, we would need a few days to create one frame, but with AI, we can experiment with four-five frames in a single day and get instant output. When you are working with strict deadlines, this is a boon. But, you need to input strong, accurate keywords for AI tools to generate the visuals you have in mind.”

Sathyaraj and director Guhan on the sets of Tamil film ‘Weapon’, which will feature an AI-generated portion

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Expect AI to alter every stage of film making, including costumes. Mohamed Akram A of OrDrobe Apparels says that the Indian film industry will soon embrace AI to transform fashion in their projects and promotional activities. “Algorithms can be used to generate costume ideas that are not only visually stunning but also relevant to the storyline and character development,” he says. “Each character’s attire can be uniquely designed to reflect their personality, era, and storyline, enhancing the overall cinematic experience.”

OrDrobe, which debuts in film merchandising with their association with the makers of the upcoming Tamil film Nanban Oruvan Vandha Piragu, is keen to actively participate in the film space. “AI can also be used in fashion trend analysis and maintaining a digital wardrobe for characters, making it easier to recreate costumes for reshoots and to ensure character continuity throughout a film,” adds Mohamed.

The cost and time saved thanks to these processes might benefit producers in the long run.

While cash-rich producers can still opt for a big VFX team to do the job, that might not be a viable option for all, especially medium and small-scale film units. Using AI tools could help them achieve 80% of the desired output at one-third the cost spent on VFX, experts say.

But it does trigger a debate on ethics: English actor-comedian Stephen Fry recently lashed out at the makers of a historical documentary for faking his voice using AI.

Does this all mean that AI will someday substitute human intelligence and labour, even in the movies? No, feels Karky. “Human creativity does have an upper edge. Our experiences and the emotions we undergo are what makes us different.”

“AI empowers creators, if used properly. But human creativity does have an upper edge. Our experiences and the emotions we undergo make us different. ”Madhan KarkyLyricist, Dialogue-Writer

“Using AI tools, you can achieve 80 percent of the same output at one-third the cost that you would spend on VFX.”Senthil NayagamAI creator

Source link

#wave #Tamil #cinema #embracing #artificial #intelligence #tools